|

BACK

SHIPBREAKERS - Page 2 saved from url=http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/2000/08/langewiesche.htm So that data will not be lost if that site moves or is removed |

|

|

|

|

A U G U S T 2 0 0 0

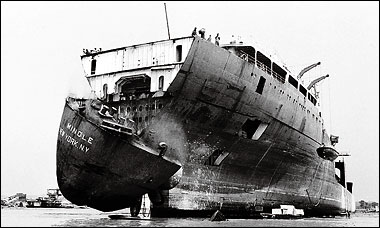

The two reporters worked on the story for more than a year. Their investigation centered on the United States, where shipbreaking had become a nearly impossible business, for the simple reason that the cost of scrapping a ship correctly was higher than the value of its steel. The only reason any remnant of the domestic industry still existed was that since 1994 all government-owned ships -- demilitarized Navy warships and also decrepit merchant vessels culled from the nation's mothballed "reserve fleet" by the U.S. Maritime Administration -- had been kept out of the overseas scrap market as a result of an Environmental Protection Agency ban against the export of polychlorinated biphenyls, the hazardous compounds known as PCBs, which were used in ships' electrical and hydraulic systems. In practice, the export ban did not apply to the much larger number of U.S.-flagged commercial vessels, which were (and are still) exported freely for overseas salvage. Hoping somehow to make the economics work, American scrappers bought the government ships (or the scrapping rights) at giveaway prices, tore into them as expediently as possible, and in most cases went broke anyway. As a result of these defaults, the Defense Department was forced to repossess many of the vessels that it had awarded to U.S. contractors. Conditions in the remaining yards were universally abysmal. The problems existed nationwide -- in California, Texas, North Carolina, and, of course, Maryland. Englund and Cohn were surprised by the lack of previous reporting, and they were fascinated by the intensity of the individual stories -- of death or injury in hot, black holds, of environmental damage, and of repeated lawbreaking and cover-ups. Cohn especially was used to working in the underbelly of society, but not even he had imagined that abuses on such a scale could still exist in the United States. Later I asked him if he had been motivated by anger or moral outrage. He mulled over the question. "I don't know that it was so much anger. I think we discovered a lot of things that were wrong and needed correcting. But I wouldn't say that we walked around angry all the time." Nonetheless the subject became their obsession. At the same time that Cohn and Englund were investigating the story, the Navy and the Maritime Administration, faced with a growing backlog of rotting hulls, were pressuring the EPA to lift its export ban. They wanted the freedom to sell government ships for a profit on the South Asian scrap market. Englund and Cohn realized that their investigation required a visit to the place where many of these ships would end up if the ban were lifted -- a faraway beach called Alang. The Sun hired an Indian stringer to help with logistics, enlisted a photographer, and in February of 1997 sent the team to India. Alang was still an innocent place: the reporters were free to go where they pleased, to take pictures openly, and to pay no mind to Captain Pandey. The reporters were shocked by what they saw -- to them Alang was mostly a place of death. And they were not entirely wrong. Soon after they left Alang, sparks from a cutting torch ignited the residual gases in a tanker's hold and caused an explosion that killed fifteen workers -- or fifty. Alang was the kind of place where people hardly bothered to count. The Sun's shipbreaking report hit the newsstands for three days in December of 1997. It concentrated first on the Navy's failures inside the United States and then on Alang. A little storm broke out in Washington. The Maryland senator Barbara A. Mikulski promptly pronounced herself "appalled" and requested a Senate investigation into the Navy's conduct. She called simultaneously for the EPA's export ban to stay in place and for an overhaul of the domestic program to address the labor and environmental issues brought up by the Sun articles. Though Mikulski spoke in stern moral terms, what she apparently also had in mind was the creation of a new Baltimore jobs program -- involving the clean, safe, and therefore expensive disposal of ships, to be funded in some way by the federal government. The Navy had been embarrassed by the Sun's report, and was in no position to counter Mikulski's attack. It answered weakly that it welcomed discussions "to ensure [that] the complex process of ship disposal is conducted in an environmentally sound manner and in a way that protects the health and safety of workers." Mikulski shot back a letter to Secretary of Defense William Cohen: "Frankly, I was disappointed in their tepid comments. We don't need hollow promises and clichés. We need an action plan and concrete solutions." Her opinion was shared by other elected officials with struggling seaports. The Maryland representative Wayne T. Gilchrest announced that his maritime subcommittee would hold hearings. The California representative George Miller said, "I feel strongly that contributing to the pollution and labor exploitation found at places like Alang, India, is not a fitting end for these once-proud ships." Miller also argued that since the Navy was paying the cleanup costs at its old bases, it should pay for the scrapping of its old ships as well. It made sense. Certainly the U.S. government could afford it. In the last days of 1997 the Navy surrendered, declaring that it was suspending plans to export its ships. Reluctantly the Maritime Administration agreed to do the same. The government had a backlog of 170 ships awaiting destruction -- with others scheduled to join them. Faced with the continuing decay of those ships -- and the possibility that some of them would soon sink -- the Defense Department formed an interagency shipbreaking panel and gave it two months to report back with recommendations. The panel suffered from squabbling, but it dutifully went through the motions of deliberation. During a public hearing in March of 1998 the speakers made just the sort of dull and self-serving statements that one would expect. Ross Vincent, of the Sierra Club, said, "Waste should be dealt with where it is generated." George Miller said, "A global environmental leader like the United States should not have as a national policy the exporting of its toxic waste to developing countries ill equipped to handle it." Barbara Mikulski said, "We ought to take a look at how we can turn this into an opportunity for jobs in our shipyards." Stephen Sullivan, of Baltimore Marine Industries, said, "We have a singular combination of shipbuilding, ship-conversion, and ship-repair expertise." And Murphy Thornton, of the shipbuilders' union, said, "Those ships should be buried with honor." In April of 1998 Englund and Cohn won the Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting. That same month the shipbreaking panel issued its final report -- a bland document that reflexively called for better supervision of the domestic industry and wistfully maintained the hope of resuming exports, but also suggested that a Navy "pilot project" explore the costs of clean ship disposal in the United States. By September of last year an appropriation had moved through Congress, and the future finally seemed clear: the pilot project included only four out of 180 ships, but it involved an initial sum of $13.3 million, to be awarded on a "cost plus" basis to yards in Baltimore, Brownsville, Philadelphia, and San Francisco -- and by definition it was just the start. This was Washington in action. A problem had been identified and addressed through a demonstrably open and democratic process, and a solution had been found that was affordable and probably about right. Nonetheless, there was also something wrong about the process -- an elusive quality not exactly of corruption but of a repetitive and transparent dishonesty that seemed to imply either that the public was naive or that it could not be trusted with straight talk. Even the Baltimore Sun had joined in: in September of 1998, when Vice President Al Gore went through the motions of imposing another (redundant) ban on exports, an approving Sun editorial claimed that the prohibition "especially benefits the poorly paid and untrained workers in the wretched shipyards of South Asia." Patently absurd assertions like that may help to explain why shipbreaking reform, despite all the trappings of a public debate, including coverage in the national press and even ultimately the Pulitzer Prize, actually attracted very little attention in the United States. The people who might naturally have spared this issue a few moments of thought may have had little patience for the rhetoric. Or maybe the subject just seemed too small and far away. For whatever reason, the fact is that the American public did not notice the linguistic nicety distinguishing the government ships in question from the much larger number of commercial U.S.-flagged ships, which would remain untouched by the reforms. So an argument about double standards, which should at least have been heard, was expediently ignored. Seen from outside the United States, the pattern was hard to figure out. India, of course, paid attention to the controversy. At Alang, where plenty of American commercial vessels still came to die, people couldn't understand why the government's ships were banned. I could never quite bridge the cultural gap to explain the logic. How does one say that the process had simply become an exercise in democracy from above? A subject had been tied off and contained.

The campaign, which continues today, was led from Greenpeace's global headquarters, in Amsterdam, by plainspoken activists who started in where American reformers hadn't ventured -- going after the big commercial shipping lines. By this past spring the activists had muscled their way in to the maritime lawmaking forums and had begun to threaten the very existence of Alang. Their task was made easier from the outset by the work of the emotive Brazilian photojournalist Sebastião Salgado, who came upon the story when it was young, in 1989, and captured unforgettable images of gaunt laborers and broken ships on the beach in Bangladesh. In 1993 Salgado exhibited his photographs at several shows in Europe and in his superb picture book Workers, which was widely seen. An awareness of shipbreaking's particular hardships began to percolate in the European consciousness, as did the suspicion that perhaps somehow a caring West should intervene. Then, in 1995, Greenpeace had a famous brush with marine "salvage" when it discovered that Shell intended to dispose of a contaminated oil-storage platform, the giant Brent Spar, by sinking it in the North Atlantic. Greenpeace boarded the platform, led a consumer boycott against Shell (primarily at gas stations in Germany), and with much fanfare forced the humiliated company to back down. The Brent Spar was towed to a Norwegian fjord and scrapped correctly, an expensive job that continued until last summer. Greenpeace had once again shown itself to be a powerful player on the European scene. It was powerful because it was popular, and popular because it was audacious, imaginative, and incorruptible. It also had a knack for entertaining its friends. When the drama of Alang came into clear view, Greenpeace recognized the elements for a new campaign. The organization was not being cynical. For many years it had been involved in a fight to stop the export of toxic wastes from rich countries to poor -- a struggle that had culminated in an international accord known as the Basel Ban, an export prohibition, now in effect, to which the European Union nations had agreed. Greenpeace considered the Basel Ban to be an important victory, and it saw the shipbreaking trade as an obvious violation: if the ships were not themselves toxins, they were permeated with toxic materials, and were being sent to South Asia as a form of waste. Greenpeace was convinced that ships owned by companies based in the nations that had signed the accord, no matter what flag those ships flew, were clearly banned from export. It was a good argument. Moreover, the shipping industry's counterargument -- that the ships went south as ships, becoming waste only after hitting the beaches -- provided a nice piece of double talk that Greenpeace could hold up for public ridicule. And Alang, with its filth and smoke, provided perfect panoramas to bring the point home. So Greenpeace went to war. It was October of 1998, a year and a half after the Sun's visit. Captain Pandey was on guard against trouble, but he must have been looking in the wrong direction. A group of Greenpeace activists got onto the beach by posing as shipping buffs interested in the story of a certain German vessel. They said they wanted the ship's wheel. But they also wandered off and took pictures of the squalor, and they scraped up samples from the soil, the rubble, and the shantytown shacks. After analyzing those samples, two German laboratories quantified what Greenpeace already knew -- that Alang was powerfully poisonous, particularly for the laborers who worked, ate, and slept at dirt level there. Greenpeace issued the findings in a comprehensive report, the best yet written on Alang. The report discussed the medical consequences of the contaminants, and described the risk of industrial accidents, which were rumored to cause 365 deaths a year. "Every day one ship, every day one dead," went the saying about Alang, and although the report's authors admitted that there was no way to verify this, it was a formulation that people remembered. Greenpeace needed a culprit to serve as a symbol of the European shipping business, and it found one in the tradition-bound P&O Nedlloyd, an Anglo-Dutch cargo line that was openly selling its old ships on the Asian scrap market. In the shadowy world of shipping, where elusive companies establish offshore headquarters and run their vessels under flags of convenience, P&O Nedlloyd was a haplessly anchored target: it had a big office building on a street in Rotterdam, and a staff of modern, middle-class Europeans, altruists who tended to sympathize with Greenpeace and would quietly keep it apprised of P&O Nedlloyd's intentions and movements. Also, because a related company called P&O Cruises operated a fleet of English Channel ferries and cruise ships, P&O Nedlloyd was likely to be sensitive to public opinion. In November of 1998 Greenpeace staged a protest at the company's offices, erecting a giant photograph of a scrapped ship at Alang along with a statement in Dutch: "P&O Nedlloyd burdens Asia with it." The press arrived, and eventually a company director emerged from the building to talk to the activists. He did not appear to be afraid or angry. He said it wasn't fair to single out P&O Nedlloyd, and he made the argument that coordinated international regulation was needed. International regulation was exactly what Greenpeace wanted -- but when the next day's paper came out with a photograph captioned "P&O and Greenpeace agree," Greenpeace denied that there had been any understanding. The truth was that Greenpeace needed resistance from P&O Nedlloyd, and it would have had to rethink its strategy if the company had submitted to its demands and obediently stopped scrapping in Asia. But of course P&O Nedlloyd did not submit -- and, for that matter, could not afford to submit. After its brief attempt at openness, it went into just the sort of sullen retreat that Greenpeace might have hoped for. Greenpeace staged a series of shipside banner unfurlings, and it dogged a doomed P&O Nedlloyd container vessel, appropriately called the Encounter Bay, as it went about the world on its final errands. Millions of Greenpeace sympathizers watched with glee. P&O Nedlloyd was so unnerved by the campaign that in the spring of last year it apparently painted a new name on a ship bound for the Indian beach, in order, perhaps, to disguise who owned it. Greenpeace found out and shouted in indignation. When P&O Nedlloyd then refused to comment, it began to look like an old man turned to evil. This made for good theater -- especially against the backdrop of the ubiquitous pictures of Alang. With public opinion now fully aroused, the Northern European governments began to move, introducing the first dedicated shipbreaking initiatives into the schedules of the European Union and the International Maritime Organization -- the London-based body for the law of the seas. In June of last year the Netherlands sponsored an international shipbreaking conference in Amsterdam -- a meeting whose tone was established at the outset by an emotional condemnation of the industry by the Dutch Minister of Transport. It was obvious to everyone there that the movement for reform was gathering strength. It was hard to know what changes would result -- and which shipbreaking nations would be affected. But the reformers were ambitious, and their zeal was genuine. I thought Pandey had reason to be afraid.

At the central train station in Amsterdam a few days later I met Parkinson's opponent, a leader of the Greenpeace campaign, Claire Tielens, a young Dutch woman with a walker's stride and an absolutist's frank gaze. We went to the station café and talked. I asked her if she had visited India yet, and she said no, but that for several years she had been a reporter for an environmental news service in the Philippines, so she knew about Third World conditions. I said, "Why did you choose Alang? Why does it seem worse to you than the other industrial sites in India?" She answered, "Because here there is a very direct link with Western companies." "But if it's Western companies at Alang, versus Indian companies somewhere else, what difference does it make to the world's environment?" "Because those Western companies pretend to us here with glossy leaflets that they are so environmentally responsible. And it is a shame when they export their shit to the developing world." "But from your environmental point of view," I asked, "what difference does it make who the polluter is, and whether he's a hypocrite or not? I mean, what is it about shipbreaking? And what is it about Alang?" I kept phrasing my questions badly. She kept trying to answer me directly, and failing, and going over the same ground. Without intending to, I was being unfair. She should have said, "We needed to make some choices, and so we chose Alang. It was easy -- and look how far we've come." I think that would have been about right. Instead she said, "Even by Indian standards, Alang is bad." But India has a billion people, and it is famously difficult to define.

(The online version of this article appears in four parts.

Photographs by Claudio Cambon. Copyright © 2000 by The Atlantic Monthly Company. All rights

reserved. | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| |

|

|